Researching the history of plants takes me down many roads, and the most interesting paths include the trials and tribulations of special people who are driven by an obsession, a desire or simply a need to advance knowledge for the rest of us. This is a story about two people, born nearly 100 years apart and a mutual desire to conquer the same plant. One was an intrepid and distinguished artist; the other is a young botanist/researcher who has spent much time at Edison and Ford Winter Estates.

Some readers may be acquainted with the epiphytic family of plants we collect and grow at the estates known collectively as “jungle cactus.” For the unfamiliar, this group of plants is native to tropical regions of the New World, from deep within South American rainforests to arid mountain plains and encompasses the well-known Christmas Cactus, Mistletoe Cactus and Dragon Fruit.

Several of our jungle cactus are flat-leaved epiphyllums including Epiphyllum hookeri, Epiphyllum oxypetalum and Pseudorhipsalis amazonica. The former two are night bloomers that produce large stunning white flowers that open for a single evening, quite similarly to the subject of this story. The latter develops small pinkish-blue flowers that resemble the flame on a lighter, hence its common name, Blue Flame. All three grow with flat stems – from the narrow leafed oxypetalum to the wide leafed P. amazonica, where this kind of structure allows these jungle cacti to wrap around host trees in a symbiotic relationship.

As our collection has grown and prospered, there is one elusive, extremely rare flat-leaved jungle cactus that we seek to propagate – the Amazon Moonflower or Strophocactus wittii. A few years back, I was gifted a small piece of plant from one of our vendors (Brian from Tropiflora), but it did not survive its first summer here. When I shared this information with him, he promptly gave me another Strophocactus, allowing us to employ improved cultivation techniques, which have resulted in a thriving specimen. So far, we have had it growing successfully for two years. Brian, on the other hand, lost his entire collection during Hurricane Milton. We feel it is only fair to protect, nurture and propagate this rare epiphyllum with the goal of replacing his gift.

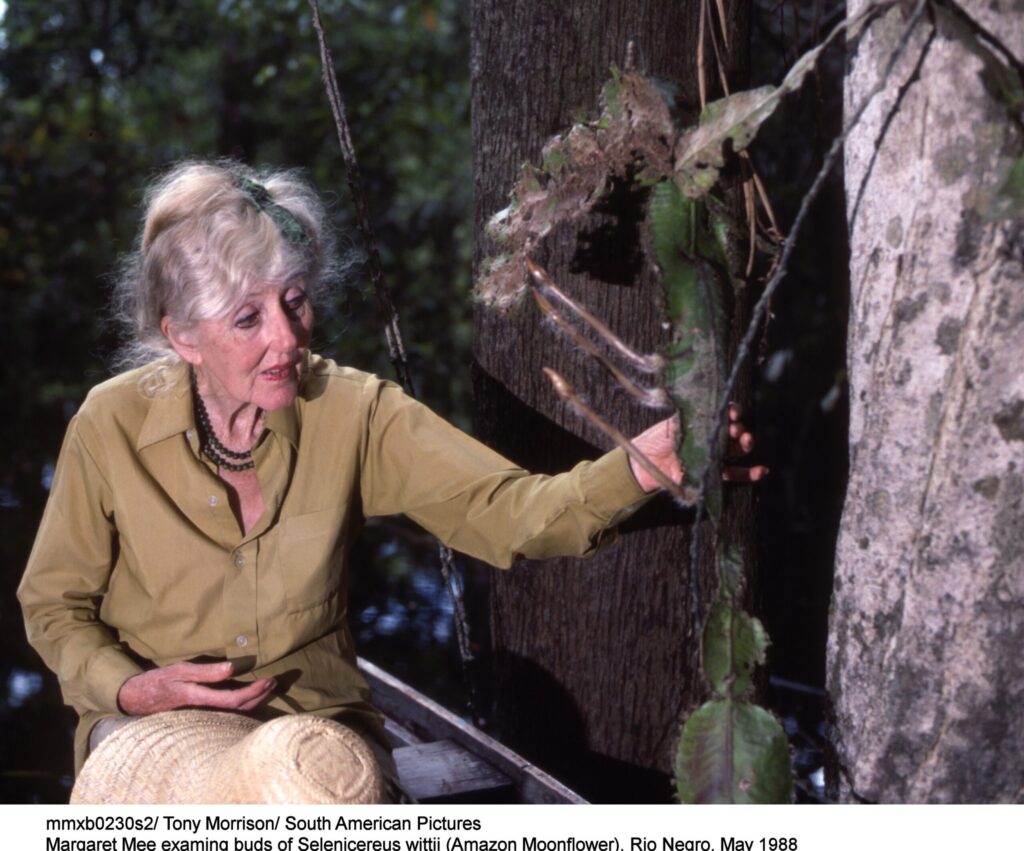

This month, I relish the efforts of the late Margaret Mee – the renowned and intrepid botanical artist who, at age 78 and with two recent hip replacements, undertook her Journey Fifteen. Mee had devoted over 30 years of her life documenting the flora of South America and had yet to catch the rare Amazon Moonflower in bloom and memorialize it in watercolor. Following an extraordinary life of chronicling and raising the alarm of rainforest destruction, little did she know this would be her final journey into the Amazon.

Impressed by her extensive work in Brazil, British naturalist and filmmaker, Tony Morrison decided it was time for the BBC to underwrite a documentary on her 30 years of work. In 1976, Mee had received the Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for her work on Brazilian botany. On approach, Tony inquired of Margaret – What is your greatest ambition? Without hesitation she replied, to paint the Strophocactus in bloom. The plant had already been collected and identified by a German plant hobbyist named N.H. Witt, but no one had ever witnessed it blooming in its native habitat.

Originally, the BBC supported the concept of filming the documentary on location, far up the Rio Negro from the port of Manaus, Brazil. Upon reflection by people unknown, the BBC backed away from the project, citing reservations due to Mee’s age and health. Undaunted, Tony Morrison took his idea to National Geographic – only to be turned away again. The groundbreaking filmmaker would not give up and neither did Margaret.

Tony and his wife, Marion Morrison, used their own funds and created Nonesuch Expeditions to fulfill their collective ambition and document the expedition of Margaret and crew into the Amazon to find her Moonflower in bloom and provide the opportunity for her to paint the rarified flower in situ.

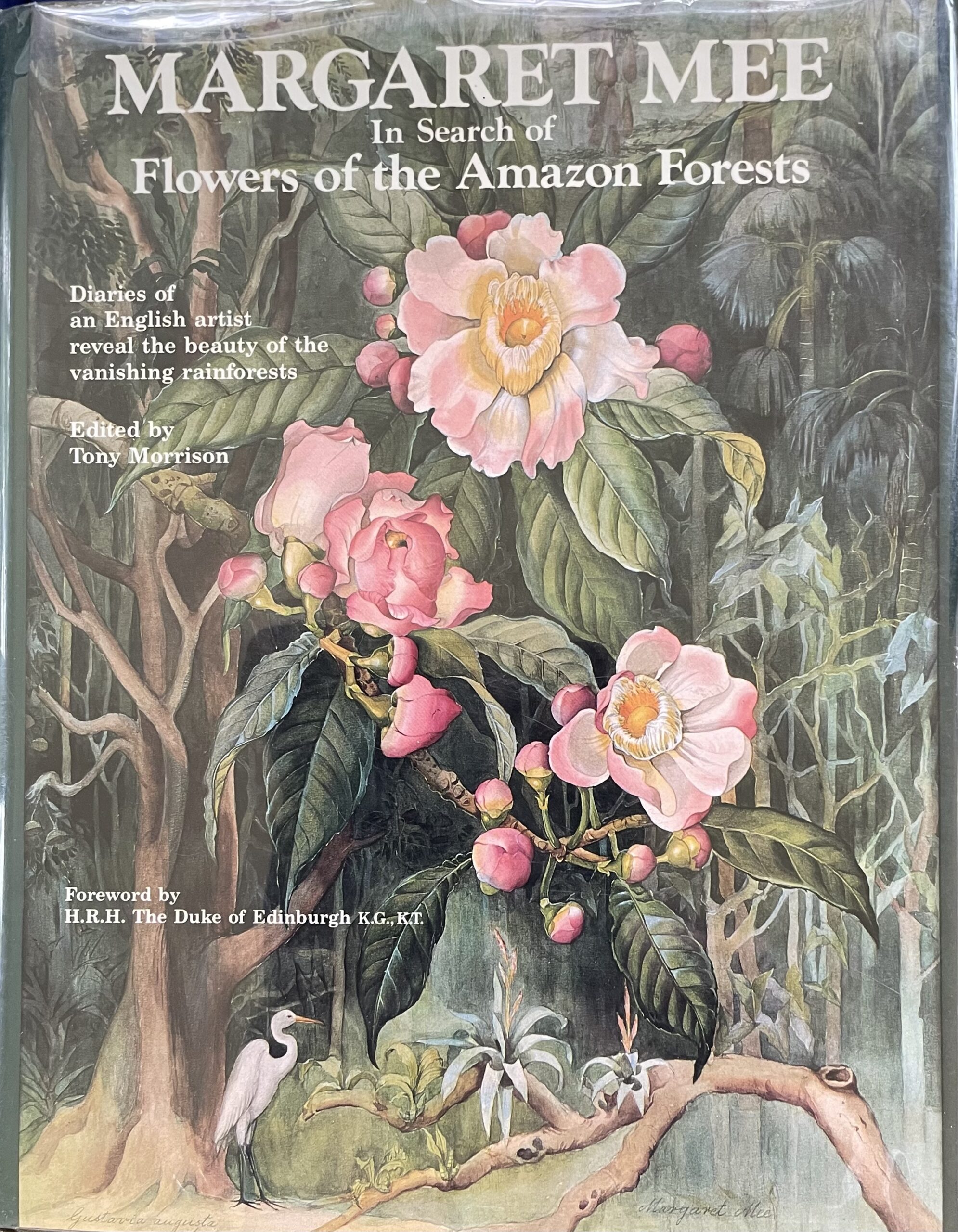

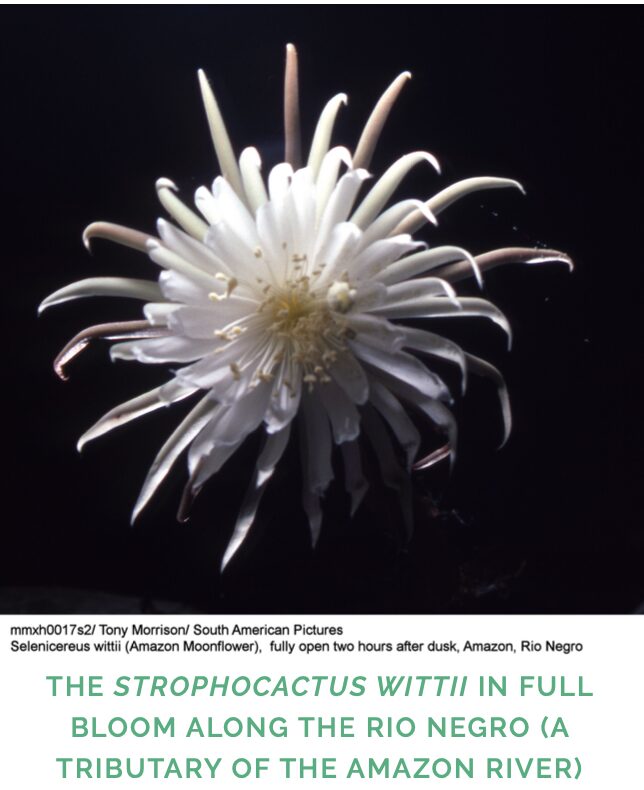

The story is vividly captured in “Margaret Mee In Search of Flowers of the Amazon Forests,” a collection of her paintings and Tony’s photographs, edited by Tony Morrison. Margaret travelled nine hours in a hammock to ease the pain in her hips, together with Tony and crew in a flat-bottomed houseboat, down the Rio Negro to a small house which would serve as basecamp. Closely monitoring daily reports of bud development supplied by local spotters, the resolute crew set out one morning at dawn and found the flat-leaved Strophocactus wrapped around tree trunks in the 400-island freshwater archipelago, the Archipelago of Anavilhanas. (Through the enlightenment provided by Margaret Mee, this area is now a protected World Heritage site.) As daylight gave way to dusk, darkness settled in quickly under the dense canopy. Margaret, perched in a garden chair on the roof of the boat, began sketching the plant, loaded with buds. Sure enough, shortly after the darkness was complete, the dramatic unfolding of the flower commenced. The light intrusion from the film cameras was enough to stop the flowers from opening. Thankfully, a full moon that night allowed sufficient light for Margaret to complete her sketches of the stunning flowers that fully opened by midnight. Without ever touching, measuring or handling the plant, she called upon her extraordinary technical ability to produce the accurately colored and dimensioned plant on paper. (During the time of Mee’s work on this plant, it was known as Selenicereus wittii but today the accepted scientific name is Strophocactus wittii.)

Fully aware of how remarkable her experience was, Margaret finished the watercolor paintings in her apartment in Rio de Janeiro and personally hand carried them back to London in July of 1988, for inclusion in her and Tony’s upcoming book. In November of 1988, she and her husband were to travel to London for the first major exhibition of her work and her new book at the Royal Botanic Gardens (RBG), Kew. Sadly, she perished in an automobile accident just two weeks before the exhibition opening. Today, her entire estate of artwork is owned by RBG/Kew.

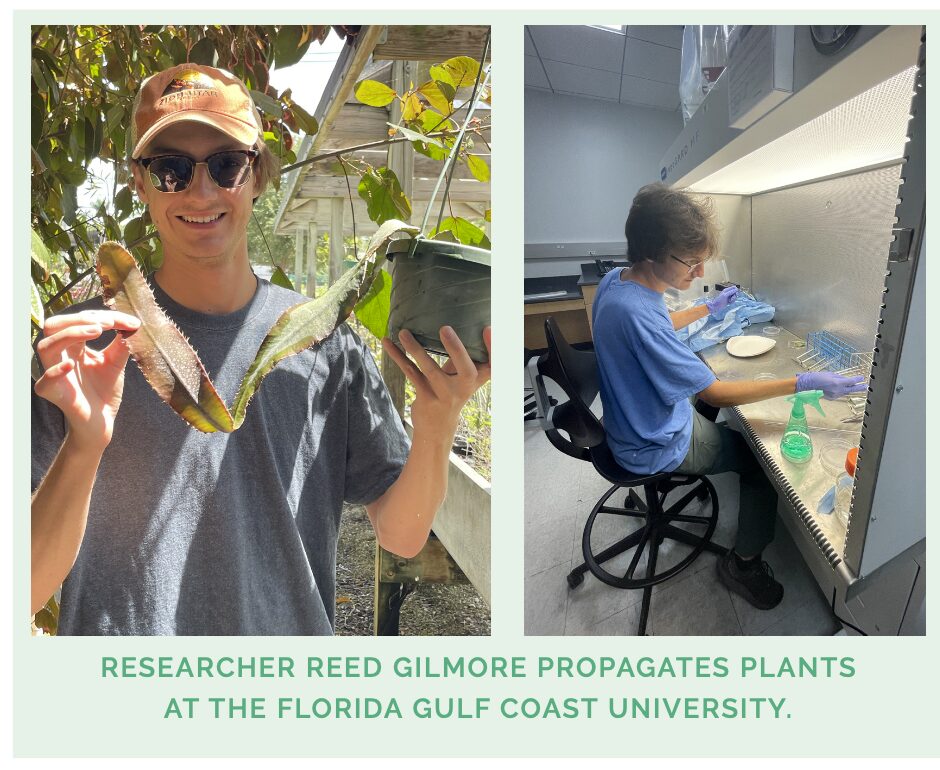

Back at the estates, we are working toward cultivating a significant specimen of the Strophocactus, and we are fortunate to have the assistance of botanist and former employee, Reed Gilmore, who has begun the task of attempting to contemporaneously propagate Strophocactus by tissue culture. This method is a time consuming and exacting effort to vegetatively reproduce the plant using the smallest amount of tissue placed in a sterile environment on a growing medium such an agar solution.

Recently, we visited with Reed in his laboratory on the campus at Florida Gulf Coast University, where he has successfully propagated endangered native cacti and the finicky Platycerium ridleyi – a rare staghorn fern. Once Reed is successful with the tissue culture of this rare jungle cactus, the estates can become a source of Strophocactus to assist other botanical gardens in the area that lost theirs to hurricanes, and of course to our original source, Brian. After that, it will be our job to protect and ultimately celebrate the spectacular blooming Strophocactus.